Looming eviction threatens the end of Skylab Gallery

Barring last-minute reprieve, the long-running, artist-operated exhibition and performance space, which has existed on the fifth floor of 57 E. Gay St. since 1998, is about to enter its final month of existence.

The last couple of times artist and filmmaker Cameron Granger returned to Columbus, he crashed on a couch at Skylab Gallery, the long-running, artist-operated exhibition and performance space located on the fifth floor of 57 E. Gay St. in the heart of downtown.

On the most recent of these visits, Granger, already feeling nostalgic, noticed a stack of flyers from past shows piled on the coffee table next to where he slept. Flipping through, he came across one advertising “Will Play for Space,” an exhibition curated by MINT Collective, the influential and now-defunct artist collective of which Granger was a part.

“And I was holding [the flyer] like, ‘Whoa, this is crazy. This is historic,’” Granger said by phone from his current home in New York City. “Just from this one show alone, how many different career paths did people take?’ And you could look at any of those flyers and do the same thing, where you can trace this insane lineage of all these creative people back to this one place.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

For more than 25 years, Skylab Gallery has existed as an essential player in Columbus’ DIY art and music scenes, providing a necessary platform for the people and sounds that might not have been able to gain a foothold elsewhere in the city. With the current tenants having recently received their eviction notice, this deeply entrenched legacy is under immediate threat.

On October 4, the four artist tenants currently occupying the fifth floor unit received a letter from Brent Wallace, chief operations officer for property management company Wallace F. Ackley, informing them that their lease would not be renewed. The letter also stated that the residents would have until November 30 to vacate the property, at which point Skylab Gallery would be no more. (Reached by phone, representatives with Wallace Ackley declined to comment.)

“I’m still holding out a glimmer of hope,” said the Columbus rapper and producer Dom Deshawn, who currently rents the space alongside writer and artist Trent Mosely, poet Mike Wright and a fourth roommate who preferred to remain anonymous. “We need to show them it’s more than just some people paying rent every month. That this place is important.”

The four are fighting an uphill battle. The lease on the unit expired in May 2024, at which point it automatically converted to month-to-month, enabling management to evict the tenants without reason by providing 30-days written notice, according to Columbus attorney Joseph Gibson.

While not legally required to give any explanation for the eviction, in emails with the tenants and Gibson, Wallace Ackley cited as a reason the results of a late-summer fire inspection, which they said uncovered issues with electrical wiring, use of multiple extension cords, improperly stored flammable liquids, and careless placement of cloth material over a lightbulb.

“Of course, our position is that these are easily correctable issues,” Gibson said. (In response to a records request, the City of Columbus Department of Building & Zoning Services and Development replied via email and said there are no current code violations on file for the building at 57 E. Gay St.)

Gibson, who serves as both a board member and the attorney for 934 Gallery, was contacted by the Skylab tenants a few weeks back in the hopes he might be able to help them secure a new lease. In a letter dated October 17, Gibson wrote to representatives at William Ackley and asked them to consider a lease renewal in which moving forward the Skylab tenants would be tasked with a lion’s share of upkeep and maintenance for the property, highlighting the space’s history and unique role within the local arts ecosystem in making his case.

“It has been in existence longer than most arts spaces in the city and is in a part of town where the city’s government and developers want people to experience art and entertainment, as evidenced by the Gay Street Corridor Improvement plan and other projects planned for the area,” Gibson wrote. “Skylab … can serve as an anchor for the neighborhood, and we ask that they be able to stay.”

“And twice I’ve been told by Wallace Ackley that they’re not willing to negotiate a new lease,” Gibson said by phone in late October. “And it’s frustrating for a number of reasons, but it feels like developers and landlords are playing Whack-a-Mole with these arts spaces, like 400 West Rich [in Franklinton] and the controversy there with rents being jacked up. … It just seems like there are fewer and fewer places people can go in a city where it’s already hard to be a working artist.”

The interior of Skylab Gallery in 1998, courtesy Chris Frey.

Artist and musician Chris Frey initially discovered the location that would become Skylab Gallery while browsing newspaper classified ads during her shift at the Wexner Center for the Arts bookstore in 1998. Frey said a fire had recently taken place in the unit, which was covered floor-to-ceiling in soot the first time she toured it, recalling how the then-landlord told her that the commercial property could best function as a storage space.

“But I could see it was this beautiful light in the middle of downtown where nothing else was happening,” said Frey, who signed a $700 per month lease to rent the fifth floor unit at 57 E. Gay St. – a building constructed in 1900 and long owned by Gilman and Sandra Kirk, who purchased it in October 1991 for $22,300, according to property records available on the Franklin County Auditor’s website.

At the time, Frey told the landlords the rental would serve primarily as a workspace. “We didn’t tell them we were going to be living there,” she said. “So, when we put in a kitchen, we told them it was because we were working around the clock, and there were nights we were going to sleep there if we were working late in the studio.”

As a way to defray the monthly rent, Frey brainstormed the idea of renting the unused section of the 3,000-square-foot unit for $40 a night to anyone who wanted to make use of the space. This attracted the attention of young artists from across the city, who embraced the anything goes potential of the outsized room beginning with “Hinjinx,” Skylab’s first-ever curated show, which took place in October 1999 and featured work by Stacy Fisher, Joe Fox, Sarah Myers and Steve Stelling.

Over time, the number of events increased exponentially, pulling Frey away from her own work and deeper into gallery management. “I ended up becoming the point person for all of these people, helping rig lights, patch drywall,” said Frey. “Whatever you could imagine a regular gallery going through, we were trying to do for kids from CCAD, or OSU, or people just living to make art. And it was all word of mouth, and as we started to have punk shows and video nights and whatever else, it helped us supplement our rent. And that was the seed. That was how we made it work.”

In those early years, the tenants took a piecemeal approach to construction, roughing out a kitchen, gradually building out bedrooms, and turning what Frey described as “a weird closet” into a darkroom, which would then serve an unintended double-duty during crowded events. “When there were 500 people packed in there, the darkroom sink turned into a urinal,” Frey said, and laughed. “It was like, ‘Okay, the boys have to step on this box and use this so the girls can have the bathroom.’”

For most of its history, anywhere from three to eight people lived in Skylab Gallery at a given time, with established roommates helping to steep any newcomers in the culture and importance of the space. “It’s been authentically handed down through groups of friends for more than two decades,” said the New York-based writer James Payne, who first attended shows at Skylab in the early 2000s and later lived there for three years beginning in 2011. “It’s a great way to run a space, honestly, and to have that institutional memory passed down.”

Each subsequent generation of residents has left its own mark, both on the physical property itself (via renovations and updates) and on the larger Columbus cultural scene. Perhaps none more so than the trio who moved into the building beginning around 2003: Doug Johnston, Grant Lavalley and Aaron Hibbs.

“I don’t know if I’d call it the heyday, because every microgeneration thinks it’s the heyday,” said Frey, who by that time had moved out of Skylab. “But I will say those guys really used the space cohesively.”

Coming into Skylab, the three had all been fixtures of the scene at BLD, an underground arts space that previously existed near the intersection of Cleveland and East Third avenues in Milo-Grogan. And they brought BLD’s freewheeling mindset with them to Skylab as they immediately set about reshaping the space, tearing out walls to create a larger central gallery and charging people $1 per swing of a sledgehammer to join in the destruction. At the same time, the tenants also ripped out most of the duct work, since they didn’t like how it looked in the reshaped gallery, which Johnston said might account for why the residents were forced to warm their bedrooms with space heaters in the early years that followed.

“It was a pretty mindful decision to put in the gallery and the proper lighting and have it be a place,” said Johnston, who lived at Skylab until 2006 or ’07. “And even with the music, it’s not like we were booking rock bands. It was definitely more performance art or stuff that otherwise had zero outlet.”

The bulk of the music bookings were made by Hibbs, who then played in the noise band Sword Heaven, with shows occurring at a pace that frequently defied explanation. At one point, Johnston said, the roommates hosted nightly shows for nearly an entire unbroken month.

“Sword Heaven was on a well-known noise label, so they got all of those people to come through Columbus, and it was just a totally different vibe than other DIY spaces, which were often campus houses that were dingy and grimy,” Payne said. “Skylab always had a bit of glamor to it. … It felt like it was in a different city. To me, growing up, Skylab was the only thing that felt like it was in New York or Chicago.”

When Hibbs, Johnston and the others first moved in, there was an older couple living on the floor below them. “And I think we kind of ruined their lives by moving in,” Johnston said. “They were actual adults, and then we moved in and within six months they were like, ‘Fuck this,’ and moved out. To their credit, they didn’t ever call the police, and they didn’t complain. They just left.”

When the couple departed, more artist friends moved into the fourth floor, later dubbed The Shelf, with other newcomers eventually spilling over onto the third floor, which Frey said had served as a field office for the Ohio Republican Party when she first rented into the building.

The artists that filled the space were all drawn by many of the same things: namely the cheap accommodations, the wildly collaborative spirit, and the downtown location, which early on afforded the residents a remarkable degree of freedom, with those interviewed describing downtown Columbus as a dead zone in the early 2000s.

“There was literally nothing there,” Johnston said, recalling how the only place that even delivered food after dark was Crazy Chicken, located in the former City Center mall and open until 4 a.m. In the years Payne lived at Skylab, he said his former girlfriend could only buy packs of cigarettes from behind the counter at one specific hotel after the clock hit 10 p.m.

This relative solitude allowed for foundation-quaking noise while also fostering a wonderful sense of the absurd. Johnston recalled the New Year’s Eve party when he and his roommates spent days making a massive ball of yarn, which they then repeatedly launched out the fifth story window onto the street below. After each toss, a partygoer would carry the ball back into the building and up the five flights of stairs, with the group repeating the process until the building had been essentially wrapped in yarn.

In 2004, Weird Al Yankovic was scheduled to play a concert at another, more established Columbus music venue, which canceled on him, leaving Weird Al’s team briefly scrambling to find him a new place to perform. “So, we totally took on the Weird Al show at Skylab. Billed it. Flyered it. Sold cash tickets,” Johnston said. “And then time of the show comes, people are there, and Weird Al never shows up. … But I think that was just the attitude we had. We were down for anything, and we never really stopped.”

Earlier this year, Johnston had a full circle moment when he found himself attending the same Emmy afterparty as Weird Al. “I went up and told him the whole story and he was like, ‘Wait, do I owe you money?’” Johnston said, and laughed. “It was like, ‘No, Mr. Weird Al, you do not owe me money. I just wanted to buy you a free drink. We’re cool.’”

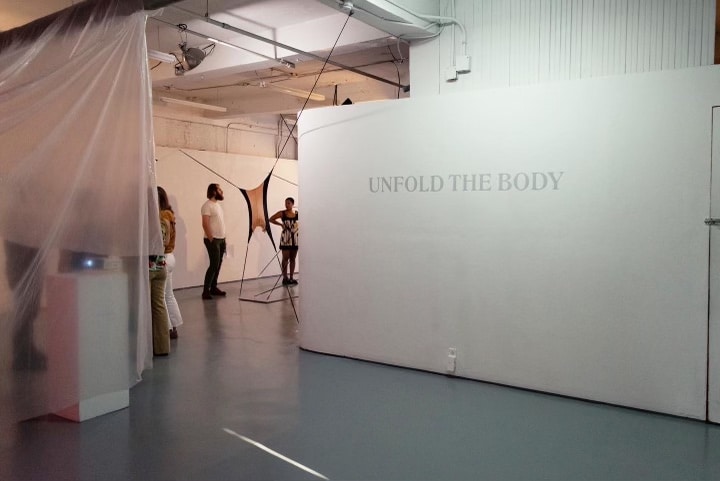

A multimedia event at Skylab Gallery, courtesy Skylab Gallery.

In the years that Payne lived in Skylab, he and his roommates scaled back the more maximalist gallery design championed by earlier generations of residents, painting the floors and the walls, redoing the windows, and leaning into an overall cleaner, more modern aesthetic that remains consistent today. And while the noise rock concerts continued, there were also more literary nights and readings, and an increased focus placed on gallery exhibitions that frequently pushed boundaries.

“Skylab is important because it’s right next to CCAD. And I taught at CCAD, and I went through CCAD, so I’m not a hater of CCAD, but the whole vibe there is very corporate and normative,” Payne said. “It’s cool to have a place like Skylab so close to expose people to a different version of what creative production can look like.”

Filmmaker Cameron Granger first stumbled into Skylab around 2012 or ’13 while attending school at CCAD, describing his initial exposure to the space as akin “to discovering fire.”

“I was like, ‘Oh, my God. I’m right down the street from my school? This feels like a whole other type of world,’” Granger said. “It felt like an introduction to … a new way of thinking about making art, and one that I was never really introduced to at all in my art school education.”

Granger would later return to the space to explore the lingering impact of his school years in “Grad Party,” one of his first public exhibitions, staged at Skylab in 2017. “And that was me picking through a lot of that baggage from art school,” he said. “And to be able to unpack that idea in a space that first got me thinking about how expansive art could be, that felt really cathartic.”

Both past and current residents lamented what will be lost if the November eviction moves forward as planned. “It would be so tragic to shut this place down, because it has been really out of sight but at the same time such a foundational part of so many different scenes in the Columbus arts community,” said current resident Jacqueline, a pseudonym.

“I often meet people in New York who played Skylab, and still remember it, and that’s equity that has been hard won in the cultural sphere, and something you can’t really ever recover,” Payne said. “There are some things that have a larger value in the city, in the culture, than what you can see on a spreadsheet. … And if it is gone, which I hope it isn’t, the Skylab niche won’t be easily filled.”