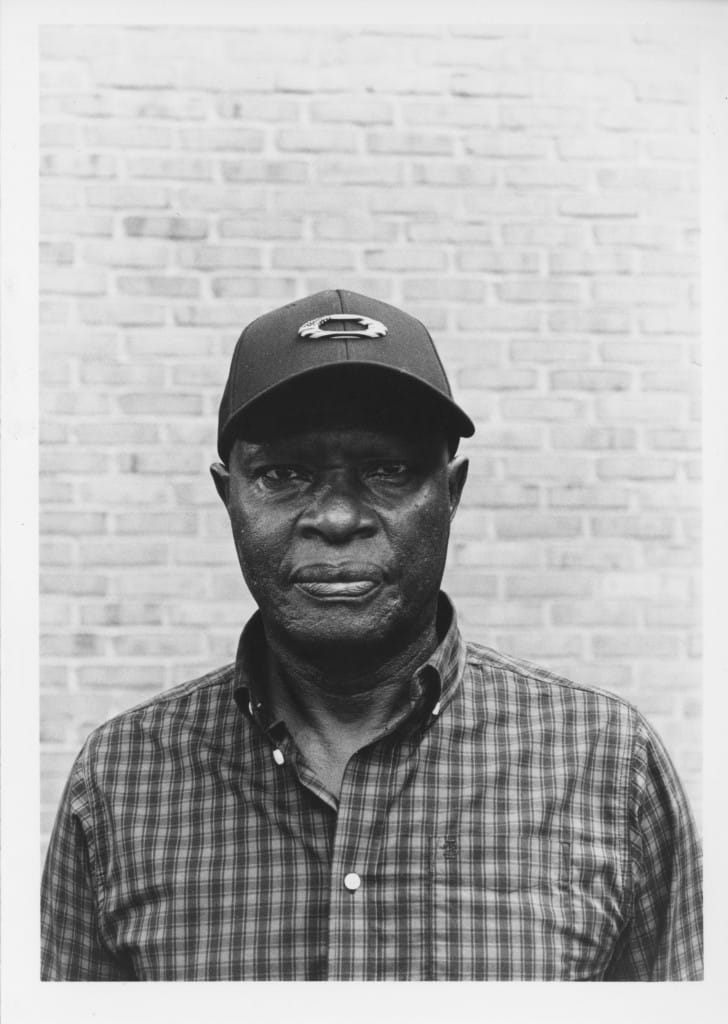

Refugee stories: Getting to know Leonard

Leonard’s tale, beginning with his escape from the Democratic Republic of the Congo through his current life in Columbus, is filled with twists and turns.

“There is no problem with someone knowing about me,” Leonard said.

But before he tells his story, he wanted to get a few things straight. First, his name is pronounced with the emphasis on the third syllable, in the way of the francophones. He grins in amusement as I try it out, giving his approval following a couple of attempts. Second, he wanted people to know that he is from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), not Congo Brazzaville, also called the Republic of the Congo. “Don’t get confused,” he said.

Leonard’s story, beginning with his escape from the DRC through his current life in Columbus, is filled with twists and turns. “My country is the richest country in Africa, so it is a lot of war there, because of mineral… gold, diamond,” he said. “I fled from my country to save my life, which was in danger.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

He landed empty handed in the neighboring country, Uganda, where he’d spend the next 14 years. “Life was not easy,” he said. “So, whenever I do remember that it makes me sad.”

Leonard’s struggles in Uganda represent the paradox refugees often experience in their search for safety. Having escaped conflict in his home country, he found himself struggling to evade harm from within the refugee camp, describing everything from the presence of poisonous snakes and rampant illness to meager rations that left him in a constant state of hunger. “Two coca bottles of oil and maize and a single cup of beans. How can you survive with that for one month?” he said.

After 14 years, Leonard arrived in the United States and allowed himself to believe that he might survive, though the road continued to be marked with potholes. The March 2020 arrival of Covid stripped him of the transportation that his first job in the U.S. had originally provided, while a work accident led to his leg being crushed by a forklift.

Injured and without work, Leonard needed help to get back on his feet, eventually finding support via Jewish Family Services, which provided financial aid and helped him secure work as a baker.

Despite having found safety in Columbus, Leonard feels that it has come at the cost of feeling at home. “Sometimes I feel that I am abandoned. I am alone in the life,” he said, contrasting this solitude with the sense of connection he felt living in his homeland. “In the Congo, your neighbor is like your brother. Even if you have a problem, you have to go to your neighbor to ask them if they will assist you if possible. But not here.”

Leonard hopes to better connect with the Columbus community by practicing his English. “I have decided for myself that I’m learning now, because I want also to perform, to be in contact with them, to communicate with them easily,” he said, sharing how he practices by speaking to himself at home, sometimes watching videos online. He also goes to a community education center two times a week to study English in a more formalized setting.

Through practicing his English every day, striving to speak it as well as he speaks his native French or the Kitooro language he learned in Uganda, Leonard is now able to share his story – something he sees as a form of advocacy for refugees both living in camps and those who have been resettled in the U.S. Recalling the trials he experienced while living in limbo, Leonard said he hopes the government will continue to welcome people from refugee camps, so they too “can have a life.”

While telling his story has emerged as a means for Leonard to advocate for others, it is also a way for him to hold tight to the good things he has experienced throughout his life, and especially the sense of community he felt in the DRC. He recounts the welcoming homes with “open doors,” the music, and the church he would attend as a younger man. Now, Leonard attends church in Columbus, which he described as a way to build a bridge to those more positive parts of his story.

“In general, every refugee is in trauma,” he said, repeating the word trauma. “If they find The One, and they embrace themself, and they start to talk, they forget.”

And then he smiled.

This is one in a series of stories collected for a project that was funded by the Baker-Nord Center for Humanities, the Case Western Reserve University Department of English, and supported by both the United States Committee for Refugees office in Cleveland and the Community Refugee and Immigration Services in Columbus.