Michael Hambouz and Ali El-Chaer strike a balance in Gazala Projects exhibition

‘It kind of feels like we’ve known each other forever. And that kindred spirit is something I haven’t always felt being in an art show. It just feels right.’

Artists Michael Hambouz and Ali El-Chaer had never met prior to a late-November video conference for Matter News. But by the time I logged into the call, the two were already hatching potential plans to meet and hang out, with Hambouz based in Brooklyn, New York, not far from where El-Chaer is currently working toward their MFA at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

“I’m 48, almost 49, and in the last couple of years I’ve discovered more people that have close roots to my family than ever,” said Hambouz, whose work appears alongside El-Chaer’s in an duo exhibition currently on display at Gazala Projects, located 90 minutes west of Columbus in Gettysburg, Ohio. (A reception for the show takes place from 3 to 5 p.m. on Saturday, Nov. 29.) “And in seeing Ali’s work, and in the little we’ve communicated, it kind of feels like we’ve known each other forever. And that kindred spirit is something I haven’t always felt being in an art show. It just feels right.”

The immediacy of this connection could be attributed in part to aspects the two share in their biographies. Both artists are Palestinian, raised by a parent (or parents) who lived for a time in refugee camps. And both grew up in the United States forced to conceal aspects of their identities. Hambouz was raised in Michigan along the Indiana border and urged by his late father to never tell anyone he was Palestinian. And El-Chaer grew up 30 miles outside of Nashville, where they attended classes in a school system they said forbade them to speak Arabic. “Post 9/11, I think everyone was very anxious about Middle Eastern people, to put it politely,” said El-Chaer, who was 6-years-old when the attacks took place.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

There are further similarities in how the two have evolved as artists, with each allowing that they started to find their respective voice only after doing away with a more traditional approach to creation. “For nearly 20 years, I worked as a pretty realist, figurative painter,” Hambouz said. “And after the passing of my second parent, I completely stopped working that way. … I think I just really needed time to find it in myself rather than being guided towards it.” (El-Chaer expressed similar sentiments, saying that they were awakened to what they could be as an artist when they pivoted from realism and attempted to capture how they felt on the canvas.)

For Hambouz, this shift could at times send him spinning into an emotional minefield, his maze-like, painted wood wall hangings containing a myriad of easter eggs both purposeful and accidental. Take one piece built around a winding milk snake that connects a river to a sea, and which surfaced layered with meanings the artist continues to unpack. “It has the colors of the [Palestinian] flag, and it used the pattern of my father’s backgammon board, which was one of the few things he was able to leave home with,” Hambouz said. “Then there’s the grass pattern in that piece, so you can look at it as the snake in the grass. And living as a Palestinian American in this country that’s a million percent complicit in the destruction of a people, I feel like I’m right in the grass with the snake. Or, you can just look at it and identify it as a snake, and walk away.”

Hambouz started to construct his walled-in works in response to the January 2023 decision by Israeli minister of national security Itamar Ben-Gvir to ban the flying of the Palestinian flag in public. As Hamouz worked, he often incorporated the image of a watermelon, which became a more recognizable symbol of Palestinian independence when Israel responded to the Hamas terror attacks of October 2024 by unleashing a genocidal war in Gaza.

“At this point, the watermelon is ubiquitous. But at that time, I was still kind of hiding in the comfort of using a symbol that nobody knew what it meant,” said Hambouz, whose work also featured earlier this year in the Urban Arts Space exhibition “Cartography,” curated by Gazala Projects founder Mona Gazala. “And so, we’re dealing with the colors of the [Palestinian] flag. We’re dealing with a watermelon. And we’re dealing with claustrophobic architectural spaces, which reference not only the walls in Gaza but also how I felt trying to talk about myself even through social media and immediately getting bot death threats.”

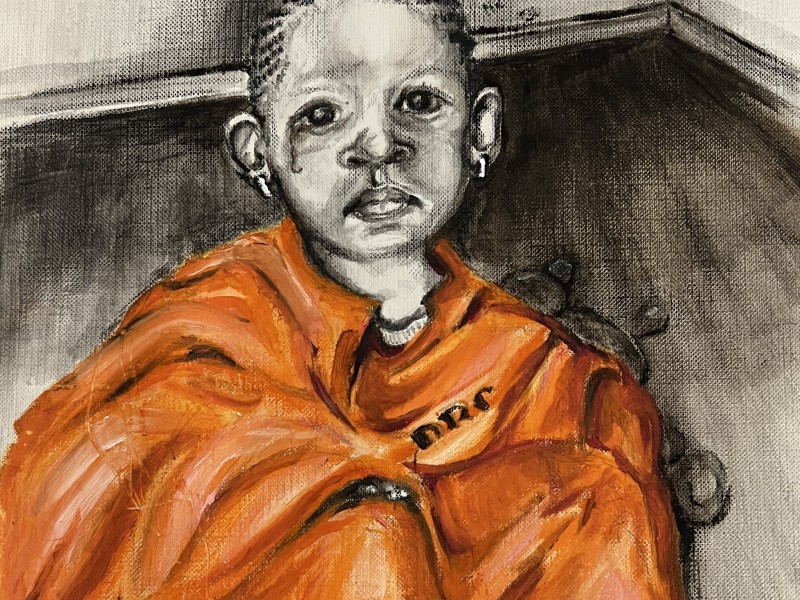

The paintings by El-Chaer currently on display at Gazala Projects come from a body of work the artist started in the aftermath of Oct. 7, incorporating aspects of the religious iconography to which they were exposed growing up Palestinian Christian outside of Nashville.

“I grew up in the South, and it’s a very Christian-dominated place, so I wanted to create art that could be understood, and that people who weren’t from Palestine could use as an entry point,” said El-Chaer, whose work is meant to give a sense of permanence to events that receive immediate attention in the moment but ultimately fade from the public consciousness. “My work now is really based on this disturbance I have with how media is consumed. I wanted to make work where it forced you to go back and realize what was happening instead of just consuming and leaving. … The Flour Massacre happened, and it was on your timeline for a day, maybe two, and now people don’t think about it anymore. And what I wanted was to make people sit with it.”

While the artists had never before engaged in conversation prior to our interview, their works have been in dialogue since the exhibition opened at Gazala Projects in early November, the proximity of their paintings drawing out different, sometimes unintended dimensions in one another. One photo sent by Gazala, for example, allows viewers to observe wheat fields painted by El-Chaer adjacent to a pair of Hambouz’s walled-in works, creating the sensation of glimpsing a more open-ended potential possible on the other side of imprisonment.

Beyond that, there also exists in the combined work a shared use of color and a technical balancing act that both artists have come to appreciate. “I feel like the differentiation in form was really familiar and interesting, too,” El-Chaer said to Hambouz. “I feel like your lines are so precise and you have so much control, where I feel very erratic in the way I create. But when I saw them together, I think I saw what Mona saw, which was a good unity and balance.”