Aryan Omar Hassan finds his way home with Henar Press

The Columbus-based publisher, which is set to release its first two books next year, hopes to draw greater attention to the more experimental strains of Kurdish literature that have long been overlooked.

Aryan Omar Hassan said the publishing establishment has for years promoted an incredibly narrow view of Kurdish literature in which the region’s writers “only had the chance to be in print via memoirs about their struggles.”

“But I know there are tons of amazing Kurdish writers,” Hassan continued, “and they don’t care to write solely about their experiences as refugees and survivors of genocide.”

These limiting narratives were further fueled by outsiders who visited the region beginning in the early 2000s and then returned home and wrote loosely fictionalized accounts based on their experiences, Hassan said, with books such as The Kurdish Bike offering simplistic, flattened views of Kurdistan’s people and culture. “And possibly the most dehumanizing thing you could do to a group of people is to not understand their complexity, and to take them as being these purely good-hearted people and nothing else,” he said. “And so, you’d have these Kurdish writers [producing] these really depressing memoirs, and then these outsiders who visit and then write about the kindly Kurdish people, and that was pretty much everything [being published]. And I knew I wanted to change that.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

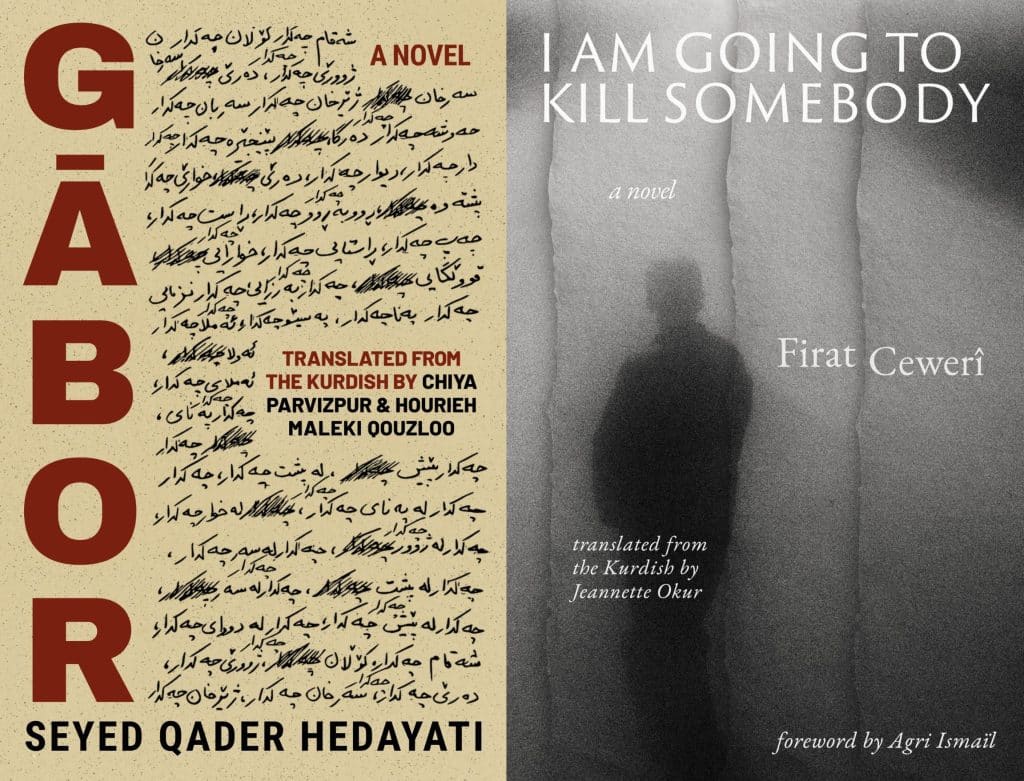

As a means of reclaiming the narrative and presenting a more three-dimensional portrait of the region, Hassan founded Henar Press, a Columbus-based nonprofit created to introduce U.S. audiences to a wider array of Kurdish authors. The press will release its first two titles next year: Seyed Qader Hedayati’s Gabor, and I Am Going to Kill Somebody by Firat Ceweri.

In tandem with the press, Hassan also built and continues to maintain the Kurdish Literary Database, a comprehensive guide to Kurdish works available translated in English, and which includes poetry collections, novels, and memoirs.

The Kurdish language is imbued with unique charms that Hassan said tend to reveal themselves in these translations, and in particular a tendency toward words that contain ideas far more expansive than their comparatively meager syllable counts would suggest. “I was talking to one of my Kurdish translator friends, and he’s translating After the Quake by [Japanese author Haruki] Murakami, and what he told me is that anytime you translate a novel into Kurdish the word count gets reduced by half,” said Hassan, who in October launched a fundraising campaign in support of Henar. “Even with the name of the publishing press, henar means pomegranate in Kurdish. … And pomegranates are kind of like the olive trees in Palestine, where it’s something that’s been stolen from us and claimed by our colonizers. … And of course I’m biased, but the word henar has this melancholy to it, and it kind of softens you when you say it. And that sound of the language is something I really want to preserve.”

Taking inspiration from fellow local publisher Two Dollar Radio, whose cofounder, Eric Obenauf, served as one early sounding board, Hassan said his intent for Henar is to feature experimental Kurdish literature the likes of which he began to doubt existed when he was a younger man. “Before I started Henar Press, I was worried that I was looking for something that wasn’t there,” he said. “There was a stretch where I was like, maybe Kurdish literature is all dark and heavy, and maybe it is all about genocide and being a refugee. But, no, that really isn’t the case, which is fantastic.”

I Am Going to Kill Somebody, for one, is threaded with the kind of dark humor to which Hassan has long gravitated, having grown up with a mother whose sense of humor remained undimmed by a lifetime spent navigating trauma. This included, Hassan said, the time she was kidnapped and held for hours at gunpoint by Iraqi morality police, who freed her only after one of her captors expressed an attraction to her. “Which is still one of the craziest things I’ve heard,” said Hassan, whose father experienced similar hardship, including the time he fled Iraq and his conscription in the Ba’athist military by purposely kicking a soccer ball over a perimeter fence during a nighttime scrimmage. “And he asked the guard, ‘Can I go get [the ball]?’ … And when they let him out, he walked or ran, and then he traveled by foot from Iraq to Turkey and on to Greece.”

Born and raised in Norway, Hassan returned with his parents to the Iraqi city of Sulaymaniyah each summer until age 10 or 11, at which point circumstances combined to throw the family into nearly a decade of tumult, with Hassan going on to log time in Sweden, England, and the United Arab Emirates before moving to Columbus for college in 2018.

“And it was terrible to move from country to country, culture to culture, language to language,” said Hassan, who noted that the frequent moves were so evenly spaced that they disrupted every stage of his life, growing within him a sense of isolation that he would attempt to quell by immersing himself in books. “And that’s kind of why I fell in love with literature, because you can lose yourself in someone else’s world. … Literature has been my way of finding my home, in the way that writers view the world, depict the world. And as long as I have that with me, I have that sense of home.”