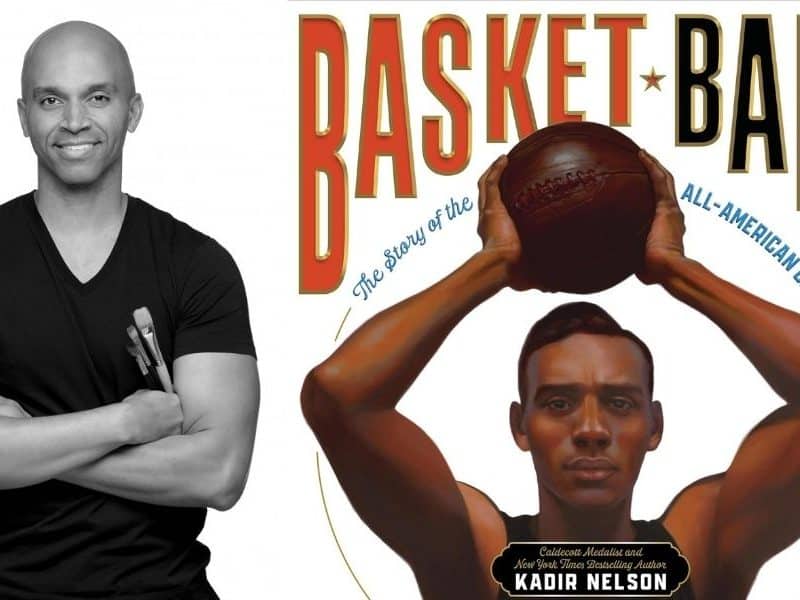

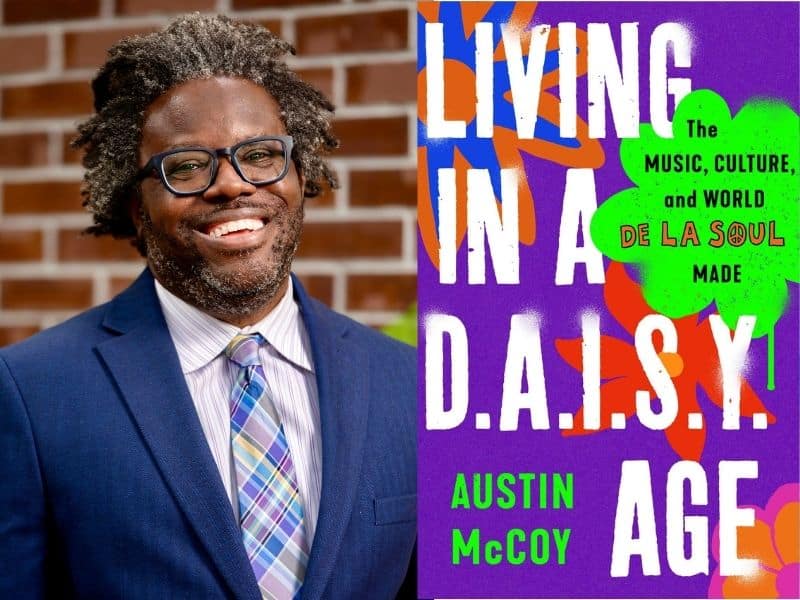

Austin McCoy grows up alongside De La Soul

The author and historian, who will be in town at Used Kids this week to discuss his new book on the pioneering rap trio, has uncovered new meaning in its work with each passing decade.

The music of De La Soul has meant different things to Austin McCoy at different times in his life.

When McCoy was in high school, for instance, the music helped him to forge a better sense of identity, owing to the reality that he could better see aspects of himself reflected in how the rap trio presented than in the other artists who then made up his CD collection. De La Soul “made it okay for young Black men … to be weird, quirky and vulnerable,” McCoy writes in Living in a D.A.I.S.Y. Age, his newly released biography on the influential crew.

“They were the first group where I could identify with them stylistically,” McCoy said. “Posdnuos wore glasses, I wore glasses. … Of course, I still loved Nas and Wu-Tang, and I loved listening to Biggie and Tupac. But De La Soul, I could identify with them more, because their music was more introspective. And yeah, at that time I was in my head a lot.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

McCoy first heard De La Soul’s music at age 8 or 9 but didn’t really begin interrogating it until he reached high school and stumbled upon the 100th issue of The Source, released in January 1998, which listed the magazine’s rap rankings in a range of categories, from greatest MC to the best albums of all time. “And me and my friends, we tried to go back and listen to as many of those albums as possible,” McCoy said.

Revisiting the New York trio’s catalogue again in his 20s and then later in his 30s, the author, educator and historian said that he started to unearth some of the weightier themes that had always existed in the group’s music but only began to resonate once he had experienced elation, heartache, love, and loss in his own life.

“The older you get, the more you obviously experience, both good and bad. And you begin to think more about these existential questions, like where you’re going in life and what you want to do and the kind of community you want to have around you. And De La Soul, they were asking those questions very early on,” said McCoy, who will appear in conversation in support of D.A.I.S.Y. Age at Used Kids on Wednesday, Jan. 28. “Then when I was in my 30s and writing this book, I went back to [the 2001 album] AOI: Bionix … and I listened to the song ‘Held Down,’ where Posdnuos is talking about the way his relationships and friendships had evolved or deteriorated and changed over time. And I was just like, ‘Oh, my God. These are issues most of us have to grow up and figure out, asking what it means if a relationship is frayed, but also how I can go back and sort of do any repair work needed in order to maintain it?’ There was a real sort of maturity there.”

McCoy said he approached research for the book like a historian, gathering a wealth of source material to capture not only biographical details and critical reactions to De La Soul but also to better grasp how the group’s music emerged from and interacted with Black and American culture in those years. The experience could be eye-opening, at times, McCoy recalling how he was struck by the mixed critical response to the group’s fourth album, Stakes Is High, from 1996, and how attitudes toward it have evolved over time.

“There were reviewers who were pretty critical of the album, because it didn’t sound like their first three,” he said. “It wasn’t as sort of carefree as 3 Feet High and Rising. And it wasn’t as sarcastic and fun as De La Soul Is Dead. And it wasn’t as weird as Buhloone Mindstate. … But when you go back and listen to the album in the context of what I considered the rap wars of the mid-1990s, De La Soul were talking about issues that pretty quickly came to pass with Biggie’s murder and Tupac’s murder. … They were talking about and commenting on all of these trends that were taking place and issuing warnings in a way I don’t think another artist or group has duplicated. De La Soul was ahead of the curve, in many ways.”

At times, being ahead of the curve proved detrimental to the trio, which experienced firsthand how art can be lost to the ether in the digital era when issues with uncleared samples and legal and financial disputes with their former label, Tommy Boy Records, kept its early albums off of streaming services until early 2023, meaning a generation of listeners essentially grew up without immediate access to its music.

This idea first struck McCoy in 2018 when he was teaching a class in hip-hop history at Auburn University where he screened an episode of “Hip-Hop Evolution” for the students that featured a segment on Native Tongues, a collection of artists from the late ’80s and early ’90s that included likeminded acts such as De La Soul, Black Sheep, and A Tribe Called Quest, among others.

“And De La Soul came on, and the students heard clips of ‘Me, Myself, and I,’ and they heard Posdnuos, Maceo, and Dave [Jolicoeur] talk, and they were like, ‘Who are these guys?’” said McCoy, who now teaches in the Department of History at West Virginia University. “And that was a lightbulb moment in realizing that … you couldn’t find this music then unless you had a hard copy, and you had access to a CD or a record or a tape. … And I don’t think I had ever considered that you could be a major artist in any genre where you put out such groundbreaking music and people didn’t have access to it.”

McCoy said this awareness added a greater sense of weight and responsibility as he researched and wrote D.A.I.S.Y. Age, instilling in him the idea that he could be cementing aspects of the group’s history in a way that might have more permanence than these increasingly temporary digital platforms.

“And I start the book by talking about that, because … I feel like it’s a demarcation moment between generations of listeners. There are those of us who grew up listening to records, CDs, and tapes. But if you grew up in the 2010s, you might have never listened to a CD before,” McCoy said. “There was this idea, like, ‘This exists, but I can’t find it, and I can’t go anywhere and listen to it readily.’ … I wanted to account for this legendary group’s absence, while also not defining them by their absence.”