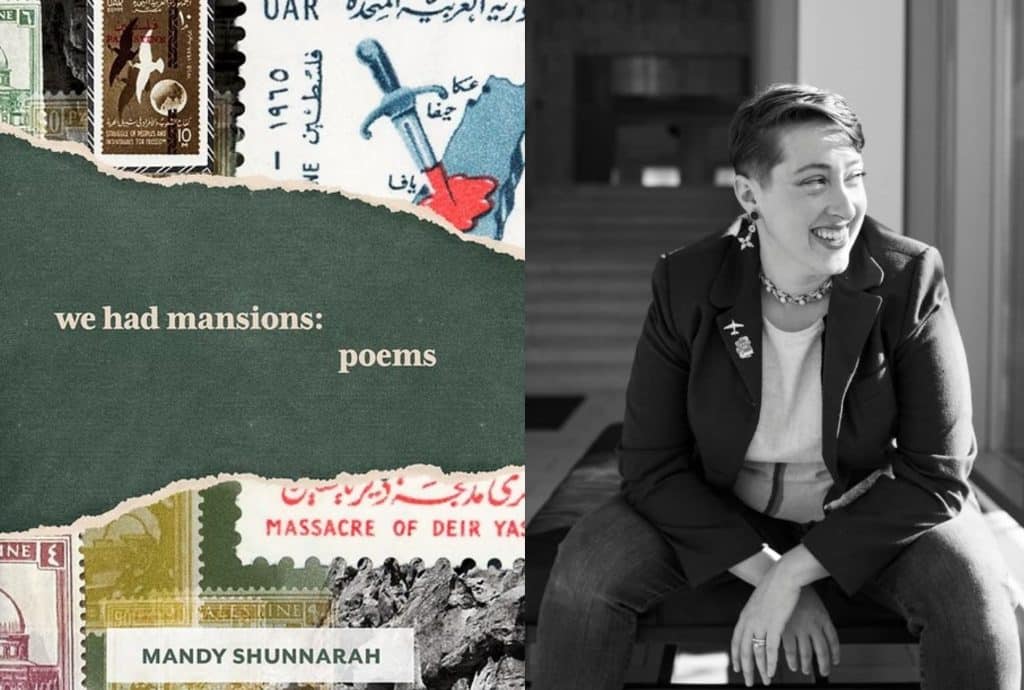

Mandy Shunnarah’s debut poetry book shares truths about Palestinians

The Columbus author will celebrate the release of ‘We Had Mansions’ at Two Dollar Radio Headquarters on Tuesday, July 22, reading alongside Nathan McDowell, Travis Chi Wing Lau, and Sara Abou Rashed.

Columbus poet (and Matter News columnist) Mandy Shunnarah knows all too well that the very labels to have shaped their childhood are laced with preconceived notions. And yet, Shunnarah bears it all on the page, courageously telling the story from the beginning and offering as many tunes as one might need to finally hear their words.

In this stunning debut collection of poems, We Had Mansions, Shunnarah does not merely settle to humanize, blame, or victimize. They confront colonizers and forced conditions; trace their Palestinian family lineage generations back; play with archive; and weave a colorful tapestry that stretches from Ramallah to Appalachia, queerness to Jesus, singularity to the collective, family to marriage, beginnings to fallouts, and so much more.

A powerful diasporic voice, Shunnarah, who will read from their collection at Two Dollar Radio Headquarters on Tuesday, July 22, reminds us of what it is to inherit disputed land and to simultaneously carry the old country and the new as their grandparents once did.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

“To escape exile, he had to exile himself. / To escape one war, he had to fight in someone else’s,’’ Shunnarah writes of her grandfather, who served in the Korean War on America’s behalf. From an immigrant to a homeowner, “this is the metaphor of America: to know freedom, but / never freedom from fear of losing everything you’ve got.’’ Even after making it, the grandparents’ fragile sense of belonging remained visible. According to Shunnarah, they were constantly nervous over sudden loss or change, often reluctant to leave the Alabama house they worked so hard to own.

One truth about Palestinians is they do not let go. “They are siblings to longing & cousins to hope,’’ writes Shunnarah, who brilliantly offers ancestors both grace and critique. It is amusing, the ironies immigrants such as their grandparents lived, from the names they gave their children (i.e., Patricia, doomed to a life of “Badrisha” in the Palestinian tongue) to plastic covered furniture they didn’t let themselves enjoy. But in this way, the lesson was learned: Do not let it happen again.

At a time when the genocide on Gaza is nearing its two-year mark – and the occupation of the land its 78th – it unfortunately never stopped happening. Violence. Displacement. Dispossession. Dismembering. For indeed, “they love us best when we’re dead,’’ is another Palestinian truth Shunnarah repeats as if a refrain that takes us both forward and back. Isn’t the world’s favorite Palestinian a dead one?

The Jesus of today is routinely stripped of origin, his existence merely symbolic. But in the more irreverent world of this book, Jesus is “just a kid from somewhere”’ steeped in community and brought up by Mary, an exhausted mother. In this spirit, Shunnarah turns toward community rather than idols, asking the world to love Palestinians just enough to keep them alive:

“In Arabic, the language that should have been my mother /

tongue, we say, I hope you wake up to goodness. On the other side /

of the world, unable to sleep for the sounds of bombing, /

mothers in Gaza pray: I hope you wake up. To goodness or not,

I just hope you wake.’’

In wrestling with the heavy inheritance of a Palestinian story, one that at first felt like a “part-time identity” and which they gradually expanded into full-time being, Shunnarah navigates the gulf between grief and hope, the Nakba and a father’s suicide decades later.

“Look at the ballistics

& see the trajectory: My father’s bullet

began not then, but when my grandparents

were forced from their land, exiled into elsewhere.

…

Follow the dotted line,

the path snipered through the air

to the point of impact, & connect the dots

to the exit wound shaped like diaspora, like America.’’

With utmost tenderness and vulnerability, Shunnarah makes explicit the aftermath of one violent event and its leading to the next. At every turn of the page, a new truth is revealed, or a connection made between generations, countries, stories.

“When it comes to partridges & Palestine,’’ for instance, Shunnarah, whose last name translates to partridge in Arabic, argues that “the persuasive popular messaging around us both is false. / The difference is, everyone knows senselessly killing birds is wrong.’’

Today, while Gazans die of starvation, let us remember that Palestinians weren’t always at the other end of a weapon. That they are just as worthy of life as anyone. That they are hospitable and hard working. Resilient and unwavering. Kind. Joyful. That they accepted refugees as kin. That they love and in loving resist that which doesn’t allow them to. That they are not poor nor violent. That they had mansions – we had mansions – and will one day soon return to the homes that were taken from them (us!) to rebuild a land and a future that are rightfully, heartbreakingly theirs. Ours.