Food insecurity on the rise in Columbus

Between widespread economic uncertainty and federal cuts to food bank assistance, more residents than ever run the risk of going hungry.

Columbus could easily be considered a success story. It’s the fastest growing major city in the state and home to a number of Fortune 500 companies, with new projects stoking hopes for continued growth, including the repeatedly delayed Intel chip factory currently under construction in New Albany.

But beneath the prosperous surface, workers continue to struggle with the rising cost of rent and stagnant hourly wages, as well as high income disparity in general. And as expenses continue to rise across the board, a growing number of residents are increasingly uncertain where their next meal will come from.

“We’ve seen record levels of people in our communities asking for help over the past few years,” said Mike Hochron, senior vice president of communications and public affairs at the Mid-Ohio Food Collective. “Many are finding that the numbers just don’t add up, or they’re one bad day away from not being able to make ends meet.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

Hochron said that economic instability, high costs of living, and inflation in sectors such as housing, childcare, and healthcare have created a perfect storm for residents already living on the edge. “In 2024, we served twice as many people in Franklin County as we did in 2019 – that’s a jump from 50,000 families a month to 100,000,” he said.

With so many people struggling, food insecurity is affecting more households than ever.

“Hunger lives in places where people don’t expect it,” Hochron said. “Hunger looks a lot like you and me and often lives right down the street. It’s people that we go to church with. It’s kids that go to school with our kids. It’s people that we work with and interact with every day.”

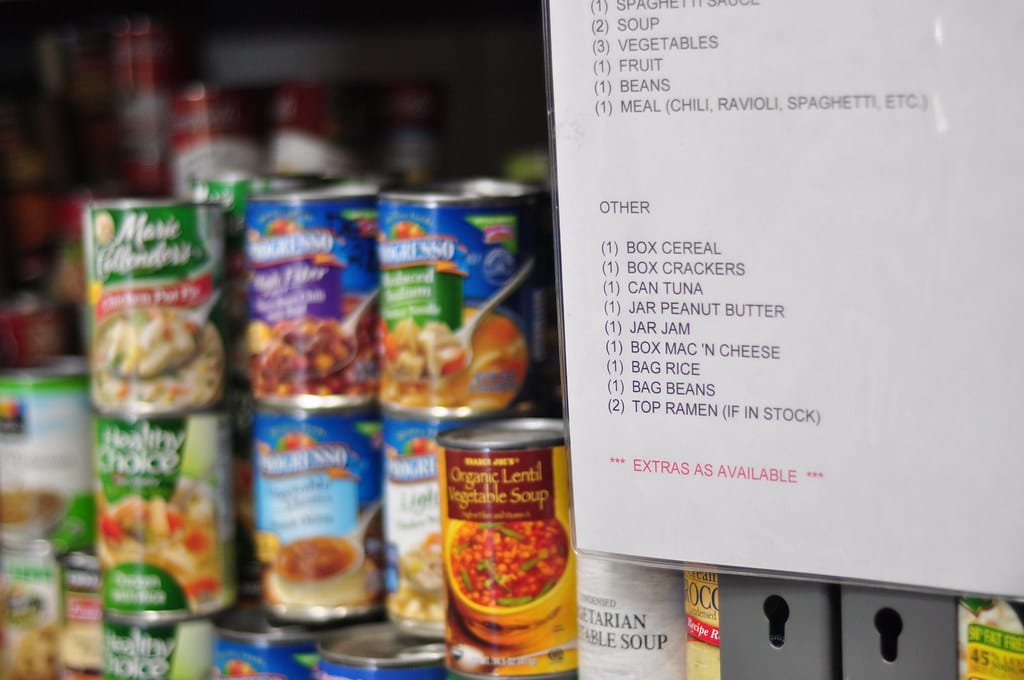

Hunger relief in the metro area takes different forms depending on a person’s need. Households living on 200 percent or less of the federal poverty level can shop at food pantries operated by organizations like the Mid-Ohio Food Collective and Lutheran Social Services. Mutual aid groups such as Food Not Bombs Columbus offer fresh produce and vegetarian food weekly with no income requirements for recipients, while nonprofits like Community Kitchen Columbus serve hot meals six days a week to anyone who walks in the door – no questions asked.

As the largest food bank in Ohio, the Mid-Ohio Food Collective supports 600 partner agencies and programs such as food pantries, soup kitchens, senior feeding sites, and after school nutrition initiatives across 20 counties. Perishables such as fruits, vegetables, meats, and dairy – products with high health impacts that can be expensive at the grocery store – make up two-thirds of the food distributed through its vast network. The organization relies on a complex ecosystem of support to keep communities fed and nourished.

“We need a consistent flow of food in order to meet that need, and it comes from a lot of places,” Hochron said. “Donated surplus from the food supply system, relationships with local retailers that have extra product, farmers who have extra supply that won’t be able to go to market – we’re able to make sure that food goes to hungry people instead of going to waste.”

State and federal government aid are also essential suppliers for nonprofits like the Mid-Ohio Food Collective, which received approximately 45 percent of its food from these sources in 2024. But even as food insecurity continues to rise in Franklin County and throughout the nation, recent cuts to federal programs have drastically impacted the supply chain that helps keep hunger at bay.

In March, the U.S. Department of Agriculture canceled funding for the Local Food Purchase Assistance Cooperative Agreement Program (LFPA), which helped the Mid-Ohio Food Collective purchase high-demand products such as protein, dairy, eggs, and produce from small and developing farmers in and around Ohio.

“We were getting $1 million dollars a year of buying power through the program,” Hochron said of the LFPA’s impact, which benefited both farmers and food banks. “Those funds were good for half a million pounds of food – hundreds of thousands of meals – that now won’t be flowing through our system.”

Around the same time, changes to a separate USDA program led to cancellations of numerous food deliveries that were scheduled to arrive throughout the summer and fall. For the Mid-Ohio Food Collective, this means that 24 truckloads carrying a total of 700,000 pounds of much-needed food won’t be showing up.

These reductions represent a staggering loss for the Columbus residents who rely on healthy staples such as chicken, milk, and cheese from the Mid-Ohio Food Collective and their partner agencies to help fill their refrigerators.

“All across the country, this is disrupting the flow of food at a time when the need for food isn’t going down,” Hochron said.

And more cuts might soon be coming at the state level.

Ohio lawmakers are working to remove pandemic-era increases in the state budget that support food banks. If approved, funding to food banks would be cut by $7.5 million per year. Although food prices across the nation rose approximately 23.6 percent between 2020 and 2024, the budget, which passed the House of Representatives in April and has now been introduced in the Senate, would return food bank funding in Ohio to 2019 levels.

For residents who are already scraping by – single parents struggling to feed growing children, working adults whose wages are outpaced by inflation, senior citizens juggling prescription costs and grocery bills on fixed incomes – these changes will have a tangible effect on their ability to put food on the table.

“Big reductions create a pretty immediate impact across the communities we serve, which is why having consistency and predictability around these programs is so important,” Hochron said, adding that anyone who wants to help can best do so by donating either their time (by volunteering with a community pantry) or their money (every dollar given to MOFC translates to the distribution of two and a half meals worth of food). “During this time of change, it’s really important that federal policies, as well as state programs and funding, remain committed to ensuring that no kid, no senior, and no family goes hungry, and that we’re supporting a robust system in the process. … We can make sure that no one goes hungry if we all stay committed and work together to make it so.”