‘Paint Me a Road Out of Here’ unpacks the power, limitations of art

Screening at the Wexner Center for the Arts on Thursday, Nov. 7, Catherine Gund’s documentary weaves together the stories of artists Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter and the late Faith Ringgold, both of whom created work that stand in opposition to the carceral system.

Art has always been there for Mary Enoch Elizabeth Baxter, who recalled absconding with her cousin’s food stamps as a 6- or 7-year-old child, later cutting them into pieces and using them to create one of her first collages. “From the time I could hold a crayon, I was exploring visual art,” Baxter said in late October.

This pursuit repeatedly proved a source of resilience as the mixed-media artist and scholar navigated various carceral systems, first becoming a ward of the state at age 12 and later spending seven months incarcerated at Riverside Correctional Facility in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, when she was arrested on the first day of her ninth month of pregnancy. Three days after being imprisoned, having been offered minimal food and no prenatal care, Baxter went into labor, entering a marathon 43-hours that culminated in an emergency cesarean section, all while shackled to a hospital bed. The experience served as one of the inspirations behind the artist’s searing narrative hip-hop video “Ain’t I a Woman,” in which she reenacts the brutal ordeal.

In the new documentary “Paint Me a Road Out of Here,” Baxter’s life in art and her struggles against the carceral system are interwoven with the career of pioneering artist Faith Ringgold, who died in April 2024 – the two serving as part of a decades-long lineage of Black creators who have embraced a pronounced social justice mission within their work.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

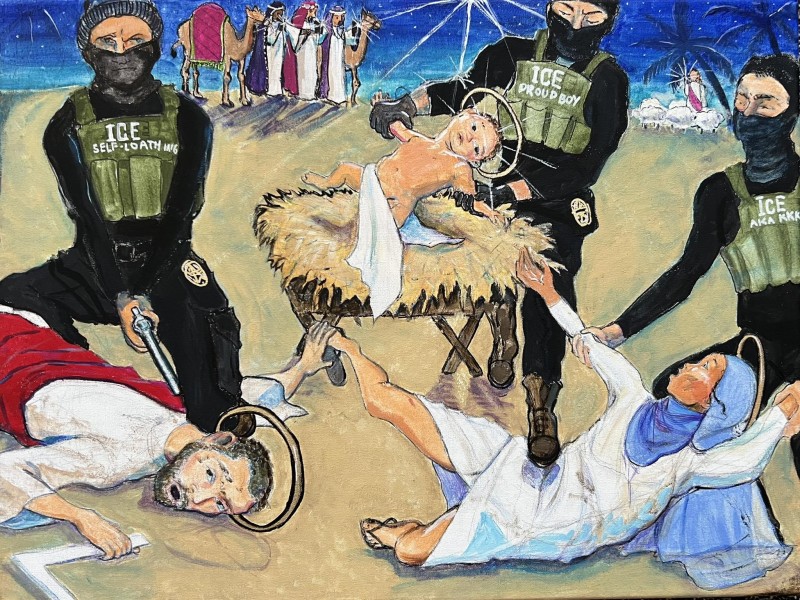

Central to the film is Ringgold’s painting “For the Women’s House,” installed at the Women’s House of Detention on Rikers Island in 1972, where it remained on display for two decades before going missing. The documentary traces the early conversations Ringgold had with incarcerated women that helped give shape to the work, along with the painting’s disappearance and subsequent rediscovery, while also wrestling with the power and limitations of art in places as inherently suffocating as Rikers.

“And I agree with both perspectives,” said Baxter, who will join “Paint Me a Road” director Catherine Gund and the Columbus-based founders of the Returning Artists Guild, Kamisha Thomas and Aimee Wissman, in conversation at the Wexner Center for the Arts following a screening on Thursday, Nov. 7. “There is a very real limitation to what art can do, because we’re still in these systems that don’t enable people to have the same access, the same equality, the same ability to thrive. … So, art has its limitations, but it’s definitely worthwhile. And I’m about long-term engagement. We have Mural Arts Philadelphia, which has done a lot of work inside of prisons, but then when people get out, they can transition into the guild program and continue to make art, create proposals, pitch projects and develop their careers.”

Part of the power that art holds, Baxter said, is rooted in its ability to affirm a person’s identity and individuality – things that authorities routinely strip away from a person behind bars. “In a lot of ways, that’s part of the punishment,” she said. “Creativity is freedom. Being able to express yourself is freedom.”

In the months Baxter spent imprisoned beginning in 2007, she didn’t have access to any arts programs, which at the time existed in limited fashion and almost solely for incarcerated men. “We live in a patriarchal society,” Baxter said. “When you go to prison, those societal constraints don’t disappear. All of that baggage still follows you.”

In the immediate wake of Baxter’s release, however, she turned to art as a means of navigating the traumas accumulated in prison, describing her pursuits in the documentary as a means to reimagine herself “outside of incarceration.”

“I gotta understand what happened, right?” she said. “I gotta figure it out. And I have to put it in my work as a way to make beauty out of the tragic, the horrible.”

Early in the film, Baxter is shown returning to Riverside Correctional Facility, tasked with collaborating on a mural painted with affirmations for the incarcerated. Returning to the site of her imprisonment temporarily sent the artist reeling back to those horrifying months, but she said the experience ultimately proved cathartic.

“It feels eerie to go in and hear the doors locking behind you, where you hear that clink but it’s also like, ‘I’ll be able to leave,’” Baxter said. “So, all of that muscle memory was there, but I was fully aware I was going home, and that took a lot of the tension away, where I could just focus on the people that I was coming in to serve. … I think it’s true that most artists first make work for ourselves, to understand the world around us and to process and heal from our trauma. And then we share it with the world, and maybe it can inspire others to use some of those same techniques.”