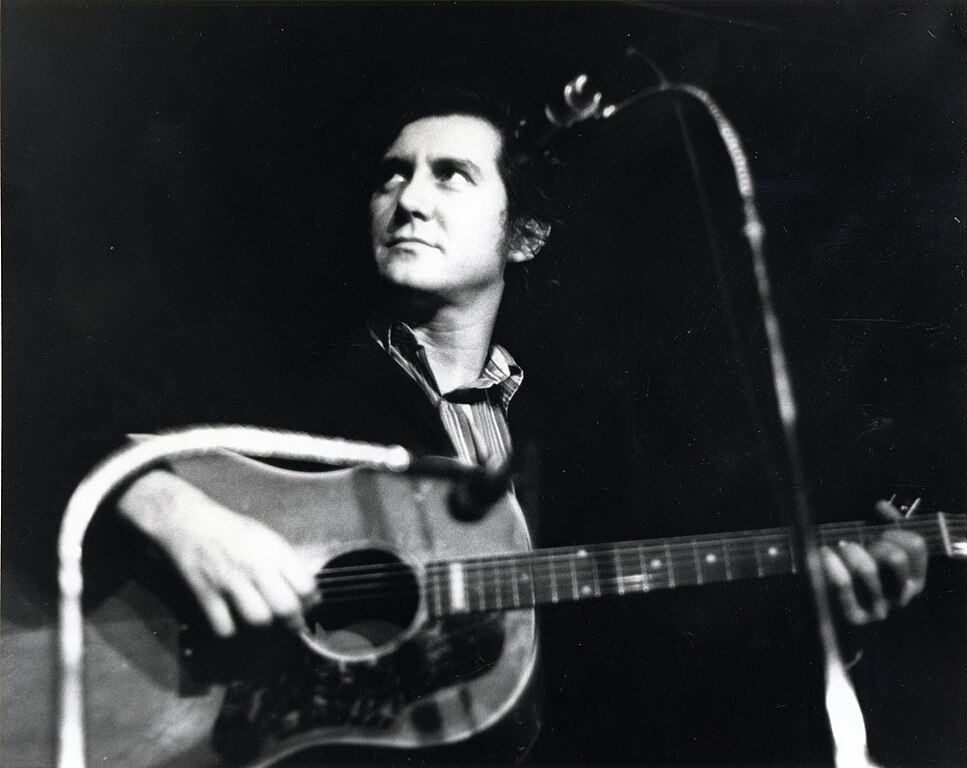

How Columbus shaped protest singer Phil Ochs

During his time at Ohio State University, Ochs became somewhat of an authority on the Cuban Revolution and its gunslinging protagonists – in addition to causing a stir in the school’s journalism department and in the bars on campus.

On an otherwise forgettable day in 1956, two teenagers sat down in a Columbus movie theater to watch a Western – one the modest son of a World War I veteran, the other who lived with his family in the working quarters of a tuberculosis hospital.

For a couple of small-town Ohio boys, movies were an escape. Soon, however, movies alone were not enough. In order to elevate the experience, the boys secured the possession of one of their family’s pistols, and when the shooting began onscreen, one of the boys would pull the pistol off-screen. In the rush of excitement, one teen accidentally fired the weapon in the theater, striking himself. The shooter’s name was Philip Ochs, and he was fortunate enough to return home to the tuberculosis hospital with only a flesh wound and a banishment from ever seeing his friend again.

There is a renewed interest of late to revisit the folk singers of the 1960s, spurred in part by the recent Bob Dylan biopic starring Timothee Chalamet. One of Dylan’s friends and contemporaries happened to be a “boy in Ohio” who used to ride his “bike down Alum Creek Drive,” as the Phil Ochs song “Boy in Ohio” goes.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

Ochs was one of the successors to the Communist folk singers of the 1930s (Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Sis Cunningham), and he adhered to their model of using music as a form of agitation, becoming a prominent protest singer and the prodigal son of American folk music.

Always a good musician, at just 16-years-old Ochs served as the principal clarinet soloist at the Capital University Conservatory of Music, though his interests stretched far beyond that instrument. Ochs listened to the radio obsessively, tuning in to the country voices of Faron Young, Ernest Tubb, Lefty Frizzell, and his biggest inspiration, Elvis Presley. In the summer of 1957, Ochs became a fixture at Columbus records shops and regularly debated with family members about their musical tastes.

But Ochs was also plagued by the impulse of humanism. During his time at Ohio State University, which he attended out of proximity and convenience, Ochs became somewhat of an authority on the Cuban Revolution and its gunslinging protagonists – in addition to causing a stir in the school’s journalism department and in the bars on campus. His new friend and roommate, Jim Glover, introduced him to the politically charged songs of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, and the Weavers. Glover’s father was a Marxist himself, even claiming to know Gus Hall, the General Secretary of the Communist Party USA who organized with the steelworkers of Youngstown in the 1930s.

In 1960, trying to embody his political optimism, Ochs won a bet that John F. Kennedy would beat Richard Nixon. His winnings were not paid out in cash, but Jim’s guitar, with Glover then obliged to teach Ochs the basics. Through a number of dinner table conversations, the Glovers imbued in the eager-listening Ochs an awareness of trade unionism, socialism, and the anti-Communist witch hunts of McCarthyism. These opinions were less than welcomed by those in the journalism department at OSU, in which Ochs was enrolled.

On campus, Ochs got involved in student organizing, joining protests against mandatory ROTC training and the politics of student government. His words could be found in most editions of OSU’s student paper, The Lantern, and the humor magazine Sundial. With a conversational writing style, he covered student government and student affairs, reviewed concerts and plays, and wrote satirical sketches centered on campus politics. Ochs soon became one of the university’s most prolific writers. His politics, however, limited the reach of his writing. Editors at The Lantern advised him to tone down his commentary, pulling him from all political stories and, despite his talent and notoriety, giving someone less radical the editor role in his senior year. Wishing to express his views unbridled, Ochs founded his own newspaper, The Word, where he published material deemed too controversial for The Lantern.

Ochs soon turned to songwriting as an outlet for these uncensored words. Flipping through newspaper headlines, he became adept at the art of writing songs based on current events. His first two songs were condemnations of the Bay of Pigs Invasion and Billy Sol Estes, a Texas millionaire involved in a price-fixing scandal. Music was largely ideological for him, and there are few songs of his that stray too far from the political realm. With a rudimentary knowledge of folk song chord progressions, Ochs played guitar and sang alongside the banjo-playing Glover in the folk duo the Singing Socialists, which began performing impromptu concerts and playing at parties around campus.

Keeping the nature of the duo obscured, Ochs set up a gig performing for a prominent Republican family in Columbus. After the duo had played a few songs, guests confronted them and accused them of being communists – an accusation that was hardly taken as an insult by the pair.

The Singing Socialists band name, however, proved short-lived. They wanted to enter competitions and get gigs at clubs where a more obscure name would work to their advantage, opting instead for The Sundowners – a reference to the 1960 Western starring Robert Mitchum. They practiced in the Ochs family’s basement and continued sporadic public shows while attending concerts at local clubs such as the Sacred Mushroom and Larry’s. The Sundowners’ career proved even shorter than the Singing Socialists. A petty fight led to Ochs to abandon Glover the night of their first big break – a gig at the opening night of the Cleveland coffeehouse La Cave.

In the summer of 1961, Ochs lined up solo gigs in Cleveland at the club Faragher’s and connected with some of the bigger names that came through the city, in particular Bob Gibson, who became a mentor in his brief encounter with the college student.

“Everybody came through that particular summer,” Ochs recalled a decade later in a radio interview with Studs Terkel. “It was a fantastic experience, because I had literally only been playing guitar for a couple of months, doing these little ditties.”

Ochs and Gibson ended up collaborating on a handful of songs, Ochs taking melodies that Gibson gave him and writing lyrics to sing over top. These collaborations became “One More Parade” and “That’s the Way It’s Gonna Be.” Ochs welcomed the connections he was making and was desperate for his hard work to pay off. In one attempt to break through obscurity, Ochs wrote a theme song for the Cleveland Indians (now the Guardians) and sent it to the local radio station that broadcasted the team’s games. It was turned down.

Back at OSU, Ochs developed a dedicated following of students who read his writings but didn’t necessarily listen to his music. In his senior year, he was conflicted about his future. Should he finish his degree in journalism – a career that was hardly welcoming to his beliefs and humor? Or should he pursue music?

“In the end,” wrote Phil Ochs’ biographer Michael Schumacher, “fate had as much to do with Phil’s ultimate decision as anything.”

Following in the paths of his musical and film heroes, Ochs opted to seek out the unknown. In the last quarter of his senior year, he dropped out of school and bought a one-way ticket to New York City, where his old friend Glover had found modest success as a folk singer. With a Sundowners reunion on the horizon, Ochs resolved to become the best songwriter in the country. (Once he met Dylan, however, Ochs retracted his statement, content with being second best.)

There is no doubt it was a handy circumstance for Ochs to find himself as a student at Ohio State. And it is perhaps the ultimate irony that a stern conservatism that then permeated through The Lantern helped to produce one of America’s most famous protest singers. And in the end, Ochs is one of the few Americans fortunate enough to escape Ohio with merely a flesh wound and a rejection letter from the Cleveland Indians.