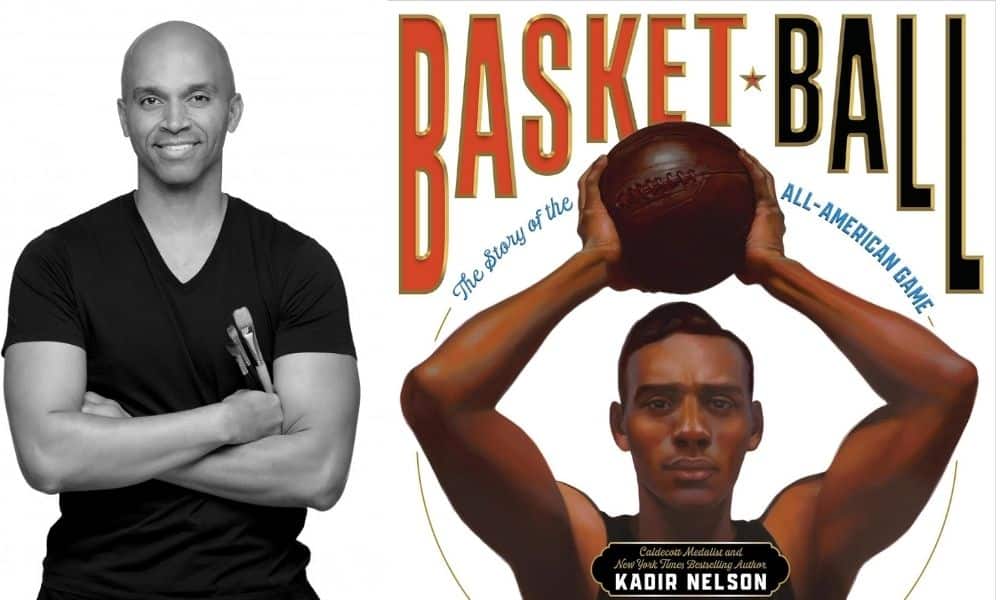

Kadir Nelson still driven by a love for the game

Following the release of ‘Basket Ball: The Story of the All-American Game,’ the celebrated artist and picture book author will appear in conversation with fellow roundball aficionado Hanif Abdurraqib at King Arts Complex on Wednesday, Jan. 14.

Kadir Nelson’s uncles introduced him to basketball as a child by letting him tag along to pick-up games. “And I remember after one of the games, one of my uncles handed me the ball, and I dribbled it. And I was maybe 4- or 5-years-old but at that moment I fell in love with basketball,” said Nelson, who translates this early passion into Basket Ball: The Story of the All-American Game, an illustrated history out this week that documents the myriad teams and players who have helped to fuel the evolution of the global sport.

Part of the challenge in this, Nelson said, involved condensing more than 130 years of history into a 100-page collection, which the artist did in part by centering his efforts on those players he described as “revolutionaries,” in that their contributions shifted how the game was played in a tangible way. “I focused on the players … where the game really had to adjust to them, literally changing the rules because of their dominance,” said Nelson, who will appear in conversation with Columbus author and fellow basketball aficionado Hanif Abdurraqib at King Arts Complex on Wednesday, Jan. 14.

Throughout Basket Ball, Nelson balances the odd off-court scene with myriad in-game depictions that capture in wondrous detail the fluidity, grace and athleticism displayed by professional players stretching from Wilt Chamberlain to LeBron James. At times, the artist said he approached his subjects as superhero-like figures barely restrained by the laws of physics, utilizing lighting and composition and exaggerating physical forms to make the static images practically ripple with movement. “That’s what art is at its core, where we’re trying to catch lightning in a bottle, or trying to deceive the eye to create these three-dimensional images with a two-dimensional form,” said Nelson, who continues to press brush to canvas for much the same reason James continues to suit up for the Los Angeles Lakers this year 23 seasons after first making the jump from high school to the pros. “I still love the practice of painting, and I still love the potential of being pleasantly surprised by something.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

Composed of more than 60 original oil paintings and deeply researched accompanying text, the book benefits from Nelson’s refusal to embrace hagiography, with passages confronting the sport’s history of racism and exclusion sitting alongside paintings of those players whose skillsets and personalities served to in time erode these barriers. “Basketball began as a segregated sport, and it kind of developed in these segregated communities – different neighborhoods and YMCAs and leagues and organizations,” Nelson said. “And it really gained momentum and strength once it became an inclusive sport, incorporating and drawing from different communities to become this juggernaut.”

Nelson, who has illustrated more than 30 picture books, traced his fondness for the form to how naturally it aligns with his love for storytelling, in addition to the impact an early exposure to art can have on children. “The first language we learn is a visual language, and picture books are really the first contact most of us as human beings have with art,” said Nelson, who recalled how as a youngster he remained awestruck by Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are. “And there weren’t a lot of words in that picture book. It starts off with this really sparse text … and then the words disappear and the story is taken over by these visuals where you can still follow it like a silent movie. … And that was a game changer for me.”

Growing up, Nelson said he wasn’t much of a reader, with the earliest books he consumed coming as the result of school assignments. This began to shift when as a teenager he read Alex Haley’s The Autobiography of Malcolm X – another formative work that shifted everything from Nelson’s understanding of storytelling to his appreciation for history, which can be seen reflected in his deepening catalog of picture books documenting everything from the stories of the Underground Railroad to the establishment of baseball’s Negro Leagues.

In an April 2024 interview with Matter News, the late Columbus illustrator Keturah Bobo spoke of the importance of representation, recalling how as a child her mother would read to her from books in which she rarely encountered characters who shared with her a physical appearance. “And you don’t realize how important that idea is unless you don’t have it,” said Bobo, who in turn embraced her brilliant, all-too-brief career as an opportunity to illustrate children’s books in which her own kids could see themselves reflected.

Nelson expressed a similar sentiment about his own work, speaking to the importance of “seeing yourself reflected in our histories.”

“And one of the most powerful, immediate ways of doing that is through visual art, whether it’s sculpture or film or illustration,” Nelson continued. “One of the things we often do as human beings is to then assemble these great visuals and hang them on the walls in museums, or to put them in films or in books. And I think it’s affirming to see yourself on that wall and to be included in these important ways that we document our history. … We’re all looking for representation in some form, and seeing that in artwork, or hearing it in music or in the stories we tell, all of those things are vastly important to feeling a sense of connectedness. And I think my choosing of subjects that resonate with me or that I aspire to be like is very much a part of that story. It’s trying to find connection to the rest of humanity, to something greater than ourselves.”