Opinion Essay: How Columbus residents pay for what industries do

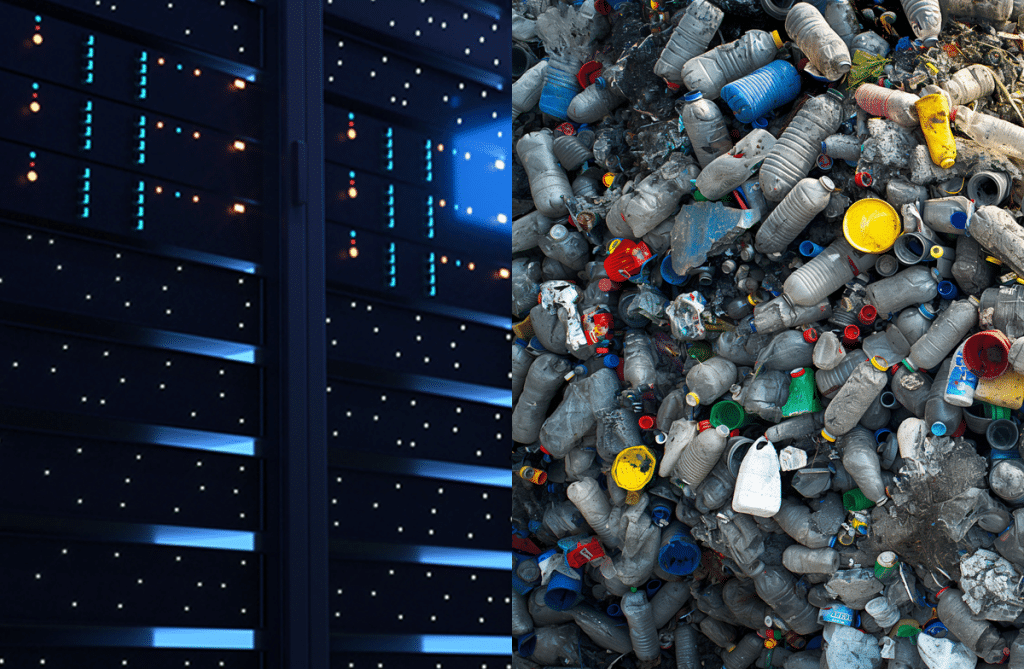

Data centers and the plastic production industry come with high costs to the public in terms of both dollars and negative health impacts.

The negative effects of plastic production and AI data centers are just two instances in which costs are passed on to the public.

If you’re not familiar with the business term “externalities,” here’s a simple definition: They’re the costs or benefits of an activity felt by a third party. An educational system fostering an informed public is an example of a positive externality. Factories polluting rivers that cause poor quality drinking water in downstream communities would be a negative externality.

Two current negative examples that we experience in central Ohio include the over-production of plastics and the massive energy needs of AI data centers. Our region is part of a national trend where plastics manufacturing, waste generation, and low recycling rates contribute to significant environmental issues. We’re also an area with very large data centers owned by AWS (Amazon Web Services), Google, Meta, and others. Those will be joined in the coming years by the planned Anduril AI weapons factory near Rickenbacker.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

Data facilities already consume huge amounts of electricity and water, and AI processing has only increased their use of both. Here in central Ohio, AEP has raised residential bills by more than $25 per month due mainly to the energy demand of new data centers. There’s also been unprecedented strain on the power grid that’s required infrastructure upgrades, with some of those costs passed on to the consumers, meaning us.

In July 2025, the Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO) approved AEP’s request for “data center customers to pay for a minimum of 85 percent of the energy they are subscribed to use – even if they actually use less – to cover the costs of infrastructure needed to bring electricity to those facilities.” One could argue that they should pay 100 percent or significantly more, but this plan may somewhat improve things.

In terms of plastic pollution, much of it exists in single-use items that take a century or more to degrade while leaching toxins. These are linked to various health issues estimated at $250 billion in annual US healthcare costs. Plastics producers have received billions in tax subsidies, diverting tax dollars from other priorities. Additionally, 84 percent of US plastics plants built or expanded since 2012 have violated air pollution limits, disproportionately affecting surrounding Black and Latino communities.

United Nations delegates recently met in Geneva to create the first legally binding treaty to address plastic pollution but failed to reach an agreement. The United States and other industrial nations strongly objected, and given the recent dismantling of federal environmental protections, it’s doubtful that any meaningful progress on this issue can be expected in the short-term.

What could we do to help here in central Ohio? To start, we should reduce our use of all types of plastics, which is easier said than done. The Solid Waste Authority of Central Ohio (SWACO)’s guidelines explain how to properly recycle materials in their system, and we should all take that information seriously. We might also take a more critical stance on AI by resisting products and services that have added it for very little benefit, or ones that infringe on existing intellectual property.

The data centers and plastics industries will no doubt continue to resist paying for the problems they’ve created, so we must advocate to address those situations. Taking responsibility for our personal uses of these systems represents just a minor step in a positive direction. What’s ultimately needed are wholesale changes to how our governments hold industries responsible for the massive, negative actions we’ve all been forced to bear.

Paul Nini is an Emeritus Professor and a past Chairperson in the Department of Design at The Ohio State University. He’s written for numerous design publications and has presented at a variety of national and international conferences.