How the poor die

The story of the overdose crisis is also a story about health care and what happens when people have limited or no access to it.

In March 1929, George Orwell, sick with pneumonia, spent two weeks in Paris’ publicly funded Hôpital Cochin.

He documented the experience in his essay “How the Poor Die,” musing that for the poor people in the hospital with him, death was lonely, painful, and bleak. He meditates on the kind of health care provided to those without resources, the experience of neglect, the loss of humanity.

“As a non-paying patient, in the uniform nightshirt,” Orwell mused, “you were primarily a specimen, a thing I did not resent but could never quite get used to.”

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

Orwell, who ultimately died from tuberculosis, suffered from respiratory issues most of his life. He was also shot while fighting in Spain, so he had extensive hospital experience. In the essay, he explores 19th century literature related to hospitals and the sadism he encountered in Paris – in particular a wrenching application of a mustard poultice.

In that Parisian hospital, people became data points, cadavers, specimens for study and manipulation. They were no longer human.

“One wants to live, of course, indeed one only stays alive by virtue of the fear of death, but I think now, as I thought then, that it’s better to die violently and not too old.” Orwell wrote. “People talk of the horrors of war, but what weapons has a man invented that even approaches in cruelty some of the commoner diseases?”

I’ve thought about this essay a lot over the years. And even more so in recent months, as the prospect for dwindling access to health care for many Americans becomes all too real. Even now, for people without access to quality health care, or for those whose access is limited, preventable death can be slow and painful.

And I’ve been thinking about this essay, in part, because the story of the overdose crisis is a story about health care, including harm reduction, and what happens when people have limited access to it. It’s a story about what happens when the response to overdose is more often rooted in morals than science.

To wit: When Purdue Pharma introduced Oxycontin in 1996, 15.6 percent of Americans were uninsured. In 2013, following Medicaid expansion, the overall number dropped to 14.6 percent. Today, that number sits at 7.6 percent.

If you drill down in the places where the overdose crisis was most acute, you will find, for example, that the uninsured rate for 0 to 64-year-olds in West Virginia was 18.4 percent in 2008. In Kentucky it was 16 percent, and in Ohio, 13.6 percent.

Today, those numbers have been cut by half or more.

With that expansion in access to insurance, Amy Rohling McGee, president of the Health Policy Institute of Ohio, said that we have also seen more people have access to health care. We’ve seen a reduction in medical debt. And we’ve seen an improvement in an ability to provide coverage to people with lower incomes.

Prior to 2013, McGee said, the landscape was rough for people who didn’t have insurance through their employer or who weren’t eligible for publicly funded insurance.

“What did people do then? They had to rely on the safety net, and that would have meant free clinics, Federally Qualified Health Centers, hospitals, the [emergency department],” she said. “And for pharmacy, there were charitable assistance programs through pharmaceutical companies, [but] those had their limitations and required more paperwork. And that was pretty much it.”

McGee ran an association of free clinics at one time, but said that access is community dependent. These clinics offer the best care that the often volunteer medical professionals can muster (gone are the days of Orwell’s mustard poultice), but often require long waits and have intermittent hours. If you happen to be sick when they are open, you’re lucky.

When you have no access or limited access, there are fewer resources for preventative care at your disposal. When you have no access or limited access and you have a mental health or substance use disorder, you can expect long waits and limited providers. And in 2024, 40 percent of adults in Ohio insured under Medicaid expansion have a mental health or substance use disorder diagnosis.

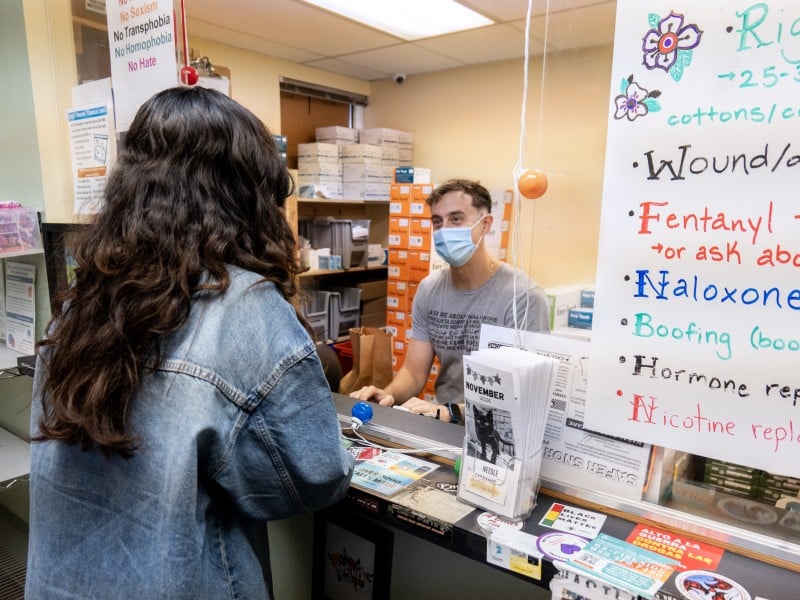

When you have no access or limited access, you might just have to rely on the kindness of strangers.

The story of the overdose crisis in Ohio is often told as a story about Big Pharma. For sure, Purdue can go kick rocks. But that story is also about health care. It’s a story about people without access to health care that could help address the root causes of pain, both physical and mental. For many, oxy was the best health care available.

It’s a story about two systems, one for people with means, and one for people without.