‘Just regular people’

There’s a long history of underground mutual aid in America that often cuts against laws and norms.

I’ve passed by the house in Granville many times. A squat, time-worn painted-red brick house with white shutters, set back from the road up on a hill. Sometimes my children would ask: What’s that shack doing there? It didn’t look like anyone lived in it, and it seemed out of place in a town of well-kept lawns and restored Victorians. It didn’t fit.

In some ways it never really fit. In the mid-19th century, an abolitionist named Edwin Wright lived there. Many of his neighbors were abolitionist sympathizers – folks who may have helped formerly enslaved people as they embarked on their brave journeys north. This stretch of what was called Centerville Street was then a sort of abolitionists row.

The folks who participated in the underground railroad communicated mostly by word of mouth so there’s scant evidence of how this secret effort operated. In later stories and records about this part of town, some folks recalled encountering fugitives who were or had been hiding. And there are plenty of stories in town of new construction that revealed possible hiding spots under stairs and in attics.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

We don’t know how many people they helped. There are few records of the work they did, or of what happened to those people as they fled north.

The folks in that red house were just regular people who felt moved to push back against unjust laws – at risk of jail time and violence from slavecatchers. And no one was paying them.

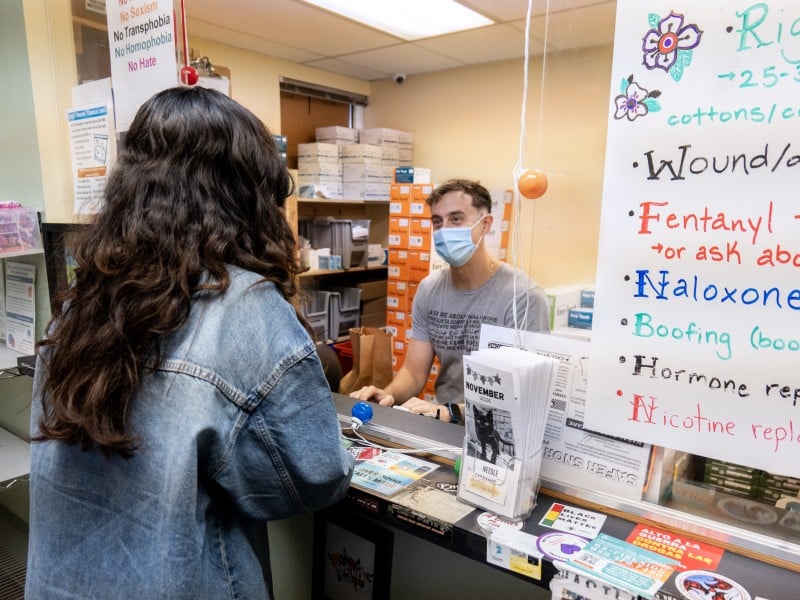

There’s a long history of this kind of work in communities across America – underground mutual aid that often cuts against laws and norms. People provided hospice care to men dying of AIDS, distributed clean syringes to IV drug users, and helped women being abused find safe spaces.

It’s an American tradition.

And there are thousands of them in cities around the United States right now – unpaid agitators, amateur protestors. These are the people standing up to armed men in masks, escorting frightened children into school buildings, and delivering food to folks too scared to open their front doors or drive to a grocery store.

President Trump says the folks on the streets of Minneapolis are paid agitators, hawking the idea that there’s absolutely no way so many people would willingly protest in negative temperatures or film and follow masked ICE agents as they gather around schools and homes.

“You know, it’s really insurrectionists and agitators, and they’re paid,” he told the press recently. “And you can tell a lot of reasons. Number one, they’re professionals…”

But these are just regular people who can see what is happening in their communities.

Like my friend in Minneapolis who has volunteered her time to help others. She was moved when stories filtered into her world about kids who wanted to go see a movie, but whose parents were scared for them to leave the house. Or about the people who’ve lived in the United States for decades, who are citizens, but are still scared to drive in their cars.

They are just people, she kept telling me when we spoke last week. They are just regular people.

So, she started paying attention. She went to a training. Joined a Signal chat. She shows up for every rally she can. It’s cold, but we’re used to the cold, she said, and we know how to dress.

On the night after Alex Pretti was shot and killed while being restrained by five federal officers, a group of people gathered on a street corner holding candles, just blocks away from that abolitionists row in Granville.

In the cold and snow, four young children stood at a street corner and waved at the handful of cars that passed. At one point they began chanting, “Change the world with love!”

Compassion is the seedbed for human dignity, the fertile ground for a more inclusive democracy. In the past few weeks, I’ve seen more compassion than I’ve seen hate. Our American history is rife with it.

I drove by that red house the other day and could see that someone is now renovating it. That’s a good thing. The house isn’t going anywhere, and neither is our history.