Life outside of Rat Park

Overcoming addiction is not always just about finding a community, but the environment certainly can play a crucial role.

In 2019, I had the opportunity to interview psychologist Bruce Alexander, pioneer of the Rat Park studies. His work led to what may seem like obvious conclusions – rats in cages with little stimulation, no peers, and no community, will use opioids that numb them from the burdens of being alive when given the option.

On the other hand, rats given space to roam, a community, toys, and games, will use opioids less often.

Alexander told me the idea for the study came from a recognition that the old drug studies mimicked what might happen if you took a human and put them in a cage (we have many examples).

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

But he was cautious. Humans are not rats. It’s not that simple.

Building a park is not that simple. We can’t just build, say, a “recovery community,” to solve a human being’s addiction to opioids. When a human walks out of that meeting or out of that recovery house, they are still in America.

I’ve been thinking a lot about Rat Park lately as I drive around my corner of central Ohio, a landscape dotted with cranes constructing Intel and myriad black box data centers. These technologies are helping to fuel gig-work in post-industrial America, driving device and social media obsession, and fostering an overwhelming sense of dislocation.

We’re not living in a cage, per se, but life feels imprisoning.

We are living outside of the park.

For someone to overcome addiction and thrive in this environment is daunting. It’s hard, Alexander told me, to be a human in this modern world. “We’re not all that strong,” he said.

Researchers have, of course, critiqued the Rat Park studies. One concern is that they foster a focus on environmental factors above all else. Overcoming addiction is not always just about finding a community, as journalist Johann Hari asserted in a much-viewed TED talk. It can be about medication. It can be about learning. It can be about biology.

But the environment certainly can exacerbate addictions: the stress of hyper-capitalism, the threat of fascism to the most vulnerable, a list of banned words by the current administration that include terms that may speak to you and your lived experience.

So, too, can policies.

Staffing cuts of between 50 and 70 percent are being considered at the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). If Congressional budget cuts are approved, Ohio stands to lose up to $31.37 billion in Federal funding for Medicaid. Almost a million people could lose their health insurance.

Not enough people have access to treatment, this could only make things worse. The Health Policy Institute of Ohio reported in January that every year 35,507 Ohioans need alcohol or drug treatment but don’t receive it because of cost, transportation, unaccepted insurance, or lack of provider availability.

Overdoses have dropped nearly 24 percent across the United States according to the Centers for Disease Control. But Sydney Silverstein, an anthropologist at Wright State University who teaches public health, told me in January that for those with a substance use disorder, the struggle persists.

Silverstein has her finger on the pulse of the overdose crisis in ways few others do. In the past 6 and a half years she has conducted about 500 interviews with people who use drugs, overdose survivors, and public health workers in Dayton.

She sits on an Overdose Fatality Review board where they conduct post-mortem case analysis of people who’ve died from overdose. Silverstein adds her insights based on her interviews and they try to figure out how they could have intervened with that person.

“And, you know, nine times out of 10, the problem started when they were a kid. And so, what do we need to do? We need to build stronger public schools that are not focused on testing and have recreation and arts and counseling and care linkage.”

But that’s not happening. So how, then, do we build the park?

It’s all the other things, the concentric circles that radiate from the same center.

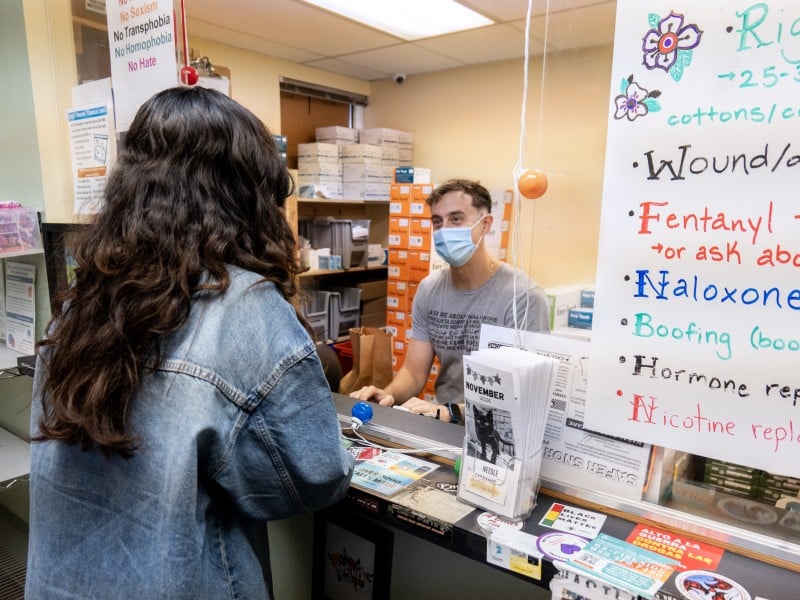

What gives Silverstein hope is all the new ways she sees people collaborating – across agencies, across differences, across communities – pulling in peers and people with lived experience, creating linkages of care.

On the night before Christmas Eve, she got a call from a woman she’s known for years. The woman was in the hospital with a xylazine wound. She was struggling. Silverstein wasn’t sure how to help her, but she was able to quickly find a peer supporter with lived experience who went to the hospital and sat with her for an hour.

It didn’t fix anything, really, she said, but it connected that woman with a compassionate listener.

There’s a network of folks who do this work that she’s connected with – people with a personal and ethical commitment to make phone calls, to sit in hospital rooms at inconvenient times, removed from any kind of grant or outcomes reporting.

“It is,” she said, “just being in community with people.”