We have to find each other: Surviving and resisting fascism through communal narratives

Garth Mullins’ new memoir, ‘Crackdown: Surviving and Resisting the War on Drugs,’ avoids the toxic self-made-man myth and embraces the power of community. There are strong lessons in it for this social and political moment.

It always begins in a garage. Some genius with an idea starts building something. Gets rich. Becomes powerful.

There’s nothing novel here. For centuries, Americans have been enamored with the bootstrap narrative. Since the nation’s founding, we have been drawn to protagonists such as Ben Franklin. People who begin with nothing and reach great heights. The success narrative, the self-made man. (And it’s usually a man.)

But there are other ways of reading, other stories we can tell.

A donation powers the future of local, independent news in Columbus.

Support Matter News

There’s a way to read Thoreau or Whitman as navel-gazing twits. Or to read them as radical empaths who went to the woods and into the streets to become better citizens, to find ways to connect more deeply with the world and to get others to follow them.

There’s a way to read Frederick Douglass’ fight with the “slave-breaker” Covey as self-made liberation. But there are also moments of collective freedom-taking in his narrative. Indeed, Douglass escaped to freedom through a network of people who despised slavery, like those people in Ohio who resisted the trade at great risk to themselves.

That is a collective narrative.

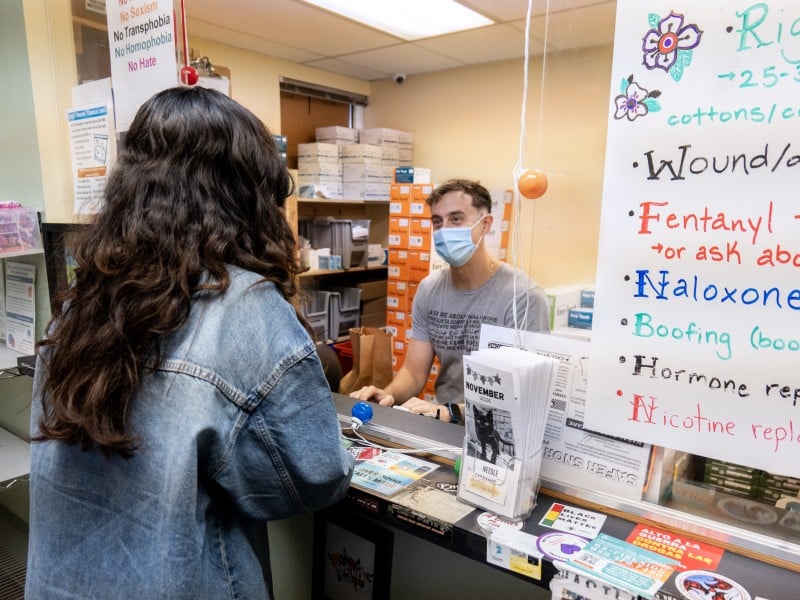

There are more – the Suffragettes, union organizers, Civil Rights activists, and, as I repeat often here, the grassroots activists who have been working for the past decades to save the lives of people who use drugs.

Garth Mullins’ new memoir, Crackdown: Surviving and Resisting the War on Drugs (Doubleday, 2025), tells this story. Though set north of the border in Vancouver, Canada, it has so much to teach readers just south of it.

Mullins is an activist, journalist, and musician. He’s an organizer with the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users and the executive producer and host of the Crackdown podcast, probably the best storytelling anywhere about the overdose crisis. A year and a half ago he spoke with one of my classes about what storytelling meant to him, telling the students that it’s central to helping people understand complex ideas and difficult truths.

“It’s the dressing on the salad,” he said.

The dressing is rich in this book.

Mullins reflects on his life and his struggles with substance use and living with albinism. He searches to find his place in a world that doesn’t let him in until he discovers others who feel the same way or who simply accept him as he is. His is a quest for connection – a story about interdependence, about mutual aid, and the work of fostering dignity.

While working in an isolated mining camp in northern Canada, he walks out onto the tundra to meditate every day, so often that the Arctic hares get used to his presence.

“In my third week, a calmness came over me and a brave one edged up to me and put its paws on my leg,” he writes. “I did this every day, the same drove of Arctic hares keeping me company. In the massive stillness of the tundra, its haunting beauty, I was momentarily okay. But whenever I got back to the mill, I was still terrified to be sober and alone with my ghosts.”

He gradually begins to understand that overdose, jail, homelessness, crime, and all of the other things that people associate with substance use are products of policy and not the moral failings of the person using drugs.

The typical “addiction narrative” is one where there’s a bottoming out and then the protagonist “gets clean.” But that sort of narrative asserts that recovery is only when one is completely abstinent from substance use. Not everyone is wired the same way. Mullins finds his hope in methadone and therapy and creation.

He finds the empowerment of activism, music, and journalism, and, ultimately, a community of like-minded people in the struggle. When he attends his first protest led by people who use drugs, Mullins is empowered and grateful.

This is a book full of gratitude, with myriad moments of grace given and received from a teacher in school, a fellow inmate in California, other people who use drugs, fellow activists, and from a loving partner.

These moments accumulate meaning as his life unfolds for readers.

Mullins does pull himself up by his bootstraps – he’s the kind of guy who wears boots, very likely Doc Martens. But he’s self-aware and knows he didn’t do it alone. He doesn’t fool himself into believing that age-old lie.

What Mullins builds is a community that centers love, not a device or an app that will make him rich.

This is a symbiotic narrative in an age of parasitic ones. Fascism craves disconnection and seizes upon the disconnected. It takes but does not give.

This is a creative, bold, and powerful narrative of resistance. It’s a narrative that begins in the garages, barns, and at kitchen tables, wherever organizers gather.

Bands also start in garages. As a teenager I played in a few that cranked out loud, obnoxious rock. But on occasion the discord would give way to harmony and rhythm. We would create something new. A feeling of ecstasy would enter the room.

Garages are also places where people organize protests. Spread out on the concrete floor painting placards, practicing chants, and preparing themselves to march at dawn.